In order to achieve the objective of progressively restoring and maintaining populations of fish stocks above biomass levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yield (MSY), the European Union agreed that the MSY exploitation rate would be achieved for all stocks by 2020.

In the North-East Atlantic and adjacent waters (North Sea, English Channel, Baltic Sea, Skagerrak, Kattegat, west of Scotland, west of Ireland, Irish Sea, Celtic Sea, Bay of Biscay, Iberian Atlantic waters), EU fisheries ministers set overall catch limits based on scientific advice.These total allowable catches are then divided into national quotas, which set limits on the amount of fish that can be landed.

The chart above shows the number of stocks that were fished according to the MSY objective (in green) and the number of stocks that were overfished compared to that objective (in red).

In the Mediterranean Sea, scientists assessed 23 stocks in 2019 (1). In 2021, no new information was available for Black Sea stocks. The previous assessments showed that six out of eight assessed stocks were overfished. Overall, fish stocks were exploited at between 170% and 270% of the MSY rate in the period from 2003 to 2018, with a slightly decreasing trend of the average (median value) from 231% to 213% of the MSY rate from 2013 to 2018.

(1) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the state of play of the common fisheries policy and consultation on the fishing opportunities for 2020 (COM(2019) 274 final).

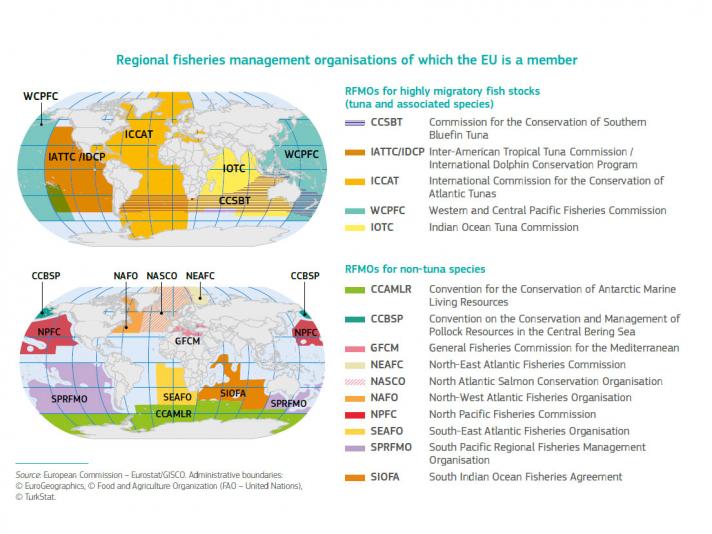

Regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs) are international bodies formed by non-EU countries and international organisations (i.e. the EU) with fishing interests in the same region or in the same (group of) species. Within these bodies, non-EU countries and the EU collectively set forth science-based binding measures such as catch and fishing-effort limits, technical measures and control obligations to ensure conservation, along with ensuring the fair and sustainable management of shared marine resources.

Today, the majority of the world’s seas are covered by RFMOs. They can broadly be divided into RFMOs that manage only highly migratory fish stocks, mainly tuna, and RFMOs that manage other fish stocks (i.e. pelagic or demersal). The collective efforts and work of RFMOs mean that stocks have improved significantly over the past few years. Under the external policy of the common fisheries policy (CFP), one of the main objectives of the EU is to contribute to sustainable fishing and support scientific knowledge in RFMOs.

RFMOs are open both to the coastal states of a region and to countries that fish or have other fisheries-related interests in that region. Represented by the European Commission, the EU plays an active role in five tuna RFMOs, 13 non-tuna RFMOs, regional fisheries bodies that have a purely advisory role and other organisations. On 23 March 2022, the EU officially became member of the North Pacific Fisheries Commission. This achievement supports sustainable stocks in the region, promotes further involvement by the EU fleets and increases to 18 the number of RFMOs and regional fisheries bodies where the EU participates. This makes the EU the most prominent actor in RFMOs and fisheries bodies worldwide.

Find out more

A transparent, coherent and mutually beneficial tool that enhances fisheries governance for sustainable exploitation, fish supply and the development of the fisheries sector with partner countries.

The sustainable fisheries partnership agreements that the European Union signs with non-EU countries provide specific EU funds to the partner country in exchange for fishing activities on the part of EU vessels. They allow EU vessels to fish in a partner country’s exclusive economic zone. Tuna agreements allow EU vessels to target and catch highly migratory fish stocks; mixed agreements give them access to a wide range of fish stocks, especially groundfish species (mainly shrimps and cephalopods) and pelagic species.

An important part of the financial contribution – sector support – addresses the development of the fisheries, maritime and marine sectors. Partnership agreements are a win–win instrument for the EU and for the partner countries.

To ensure sustainable fishing, EU vessels are only allowed to target surplus resources that the partner country is not willing to fish or not capable of fishing. In exchange, the EU pays a fee for the right to access the partner country’s exclusive economic zone, and provides sectoral support tailored to the partner country’s needs. This support aims to reinforce fisheries governance, strengthen administrative and scientific capacities, foster monitoring and control activities, and support small-scale fisheries, thereby leading to improved sustainability. In addition, EU vessel operators pay a licence fee for access. The burden of payment is shared between the EU and the industry.

Today, sustainable fisheries partnership agreements set the standard for international fishing policy. They are all centred on resource conservation and environmental sustainability, with EU vessels subject to strict supervision and transparency rules. All protocols contain a clause concerning the respect for human rights in the partner country.

The agreements are negotiated and concluded between the Commission, on behalf of the EU, and the partner country. Transparency and accountability are the driving principles of the negotiation process; the texts of the agreements are public and open to the scrutiny of other public institutions and civil society.

The EU has had fisheries agreements with Norway and the Faroes since the late 1970s, and with Iceland since the early 1990s, while fisheries relations with the United Kingdom have been covered by the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) since 2021.

The TCA covers the cooperation between the EU and the United Kingdom on the joint management of fishing activities for shared stocks, in an effort to ensure long-term sustainable exploitation and achieve economic and social benefits. The agreement, based on shared principles and objectives for sustainable cooperation, outlines the procedures for setting total allowable catches and quotas, the development of long-term strategies, dispute settlement mechanisms, the annual consultation framework and discussions through the Specialised Committee on Fisheries in order to maintain a close relationship on shared fisheries.

The fisheries agreement with Norway covers the joint management of shared fish stocks in the North Sea and Skagerrak areas, notably through total allowable catches and quotas, and, where possible, within the framework of long-term management strategies that ensure sustainable fisheries. It also includes an annual exchange of fishing possibilities. After the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union, formerly bilaterally shared stocks in the North Sea have become part of the annual trilateral consultations between the EU, Norway and the United Kingdom, in order to guarantee the continuation of fishing activities.

The agreements with the Faroes and Iceland are based solely on the annual exchange of fishing possibilities in each other’s waters with the associated access. Since the 2008 fishing season, no annually agreed exchange of quotas has taken place with Iceland and the agreement has become dormant.

Find out more

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is a major threat to global marine resources. It depletes fish stocks, destroys marine habitats, distorts competition, puts honest fishers at an unfair disadvantage and destroys the livelihoods of coastal communities, particularly in developing countries.

It is estimated that the value of illegally caught fish amounts to around €10 billion each year, corresponding to almost 20% of the value of the world’s catches.

As the world’s largest importer of fisheries products, the EU has adopted an innovative policy to fight IUU fishing worldwide

- firstly, by not allowing fisheries products to access the EU unless they are certified as legal (the catch certification scheme)

- secondly, by holding flag, coastal, port and market states responsible for their international obligations in the fight against illegal fishing (dialogues and cooperation)

The EU regulation on illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing entered into force on 1 January 2010. It relates to EU Member States and non-EU countries alike, applies to all vessels that commercially exploit fisheries resources destined for the EU market and covers all fishery products imported into the EU (with a few exemptions).

The catch certifications scheme under the IUU regulation has helped to improve the EU’s capacity to identify and deny permission for the import of fishery products from IUU sources. It allows Member States to better verify and, if appropriate, refuse imports into the EU. This is reinforced by a system for sharing intelligence, the annual publication of the EU IUU vessel list and CATCH, an IT system designed to support checks by Member States under the catch certification scheme.

Under the IUU regulation, the EU can enter into a structured process of dialogue and cooperation with those non-EU countries that have problems meeting international IUU rules, with the aim of helping them undertake the necessary reforms (see the illustration).

In this context, since 2010 the EU has entered into dialogue with over 60 non-EU countries. Thanks to this cooperation, most of these countries have improved their systems and have committed to join the EU in fighting IUU fishing.

All EU fishing vessels are governed by a legal framework and a control system that apply anywhere they fish through the regulations on fisheries control, sustainable management of external fishing fleets and IUU fishing.

Find out more